the hotel

We stayed at Planet Hollywood, just next to the mock Eiffel Tower halfway down the strip. The rooms were a very good price at around $140 a night including the unavoidable resort tax. We were given a first glimpse of Vegas's hectic, chaotic nature waiting to check in: a half-hour queue full of impatient, shouting tourists all demanding to be given priority. That's one thing every Vegas visitor shares: an insistent belief that nothing matters more than your own comfort and needs. As this Christmas trip was also doubling up as our delayed, de facto honeymoon, we were upgraded to a room with a view over the Strip, able to watch the Bellagio fountains perform every thirty minutes.the Strip

An endless array of casinos, shops, hotels, expensive restaurants, neon lights, parading tourists, slot machines, and traffic jams, its buildings towering into the night sky, the Strip represents everything Las Vegas is about. At one moment the Eiffel Tower rises majestically, the Arc de Triomphe small behind it, the next the Statue of Liberty stands next to the Empire State Building. Further down towards the airport, there's a little bit of Australia next to the Sphinx. Elsewhere, the canals of Venice offer gondola trips beneath a permanent blue sky.

An endless array of casinos, shops, hotels, expensive restaurants, neon lights, parading tourists, slot machines, and traffic jams, its buildings towering into the night sky, the Strip represents everything Las Vegas is about. At one moment the Eiffel Tower rises majestically, the Arc de Triomphe small behind it, the next the Statue of Liberty stands next to the Empire State Building. Further down towards the airport, there's a little bit of Australia next to the Sphinx. Elsewhere, the canals of Venice offer gondola trips beneath a permanent blue sky.The Strip can get a bit too much: a constant, chaotic call to action where it's almost impossible to move. In the crisp morning sunshine, @kt_canfield and I did what must be a rare thing: we carried on walking south down the Strip, away from the tourists, until we got to the "Town Square" three miles away: a complex with a park, shops, and a great bar called the Double Helix, offering a good selection of wine and whisky. To the north of the Strip lies Downtown, offering yet more casinos but in a more laid-back and approachable way - the minimum stakes here are a lot lower as well.

the tourists

Las Vegas is a fast-paced city which moves in slow motion. The tourists shuffle up and down the strip, taking photos on their iPads, distracted by the lights, the names, and the street performers - until they realise the performer is an actual, genuine homeless person. Pretty much the whole of the Middle East and a fair share of Japan was in town for the Christmas period, some of them getting in early for what I can only imagine is a terrifying New Year's Eve experience. As busy and hectic as Vegas was, many of the tourists were happy to shop, promenade, and enjoy the experience rather than merely gamble - the casinos weren't as unmanageably crowded as the strip itself.the taxi drivers

For some reason, I thought Las Vegas would be quite self-contained and it would be possible to get to places without a car. As the permanent traffic jams demonstrated, everything in Las Vegas is spread out and with a lack of public transport you need a taxi or a car to escape the madness of the strip and discover what else the city has to offer. Our taxi drivers, few of them from Vegas itself, were a rather cynical bunch; one, a "Persian" in the process of applying to be a translator at the UN, bemoaned the emptiness that gambling brought on its guests and its inhabitants, making the city a desperate competition to survive. A sobering thought when being driven back from a casino.the show

Not being a great one for shows, I opted for one called Absinthe. Located in a Spiegeltent outside Caesar's Palace, this was a riot. A series of spectacular acrobatics interspersed with very funny but extremely crude jokes, this was Vegas at its best: funny, irreverent, unforgettable, and plain bonkers.the casinos

|

| show me the money |

We stuck to blackjack, simply because it's easier than poker. However, each table has slightly different rules, which you need to be aware of either to take advantage of or to ensure you don't get stung. Taking your time to measure up each table is definitely a good idea. Instead, on our way to the hotel room we spontaneously sat down at a table with a minimum stake of $15. Within ten minutes, we had lost $160; shellshocked, we crawled into bed and fell into a deep sleep we hoped not to awaken from.

After collecting ourselves and coming up with game plan, we had much more luck the next night at the Golden Nugget, in downtown Las Vegas. More relaxed, with friendly, helpful croupiers and lower stakes, I actually came away with some money.

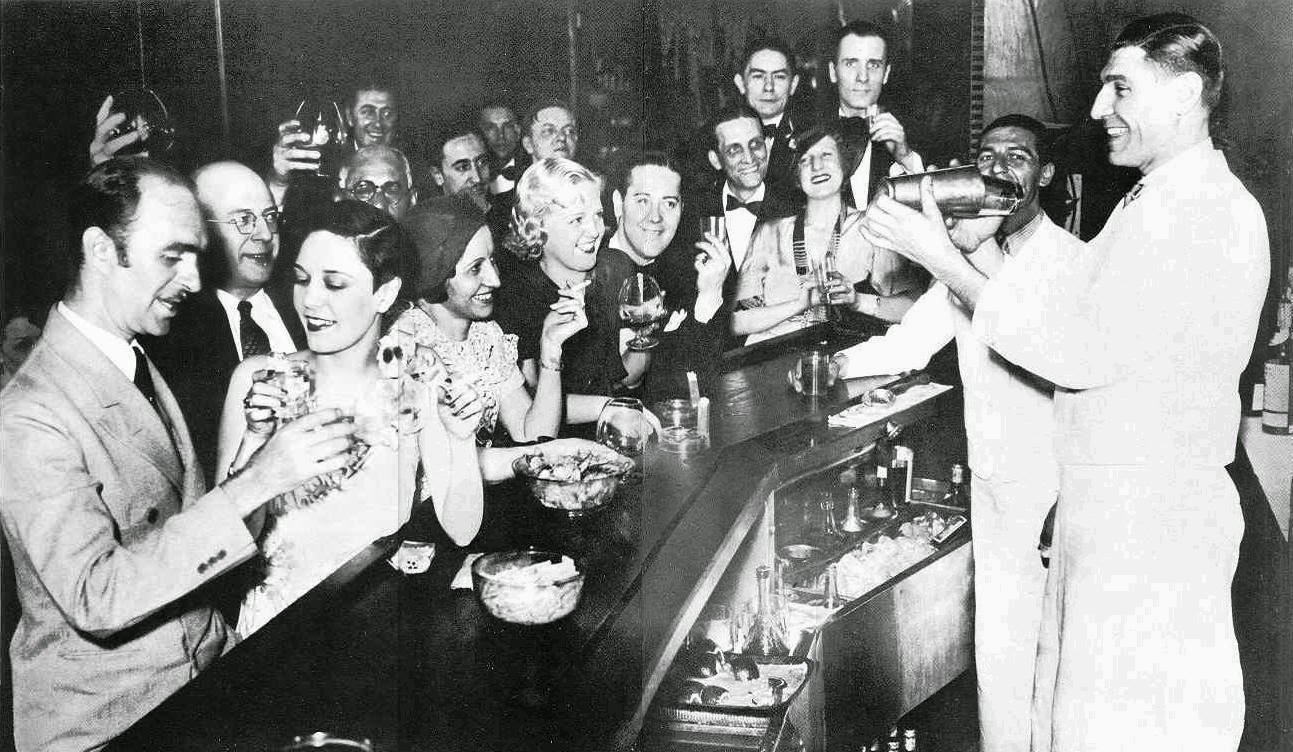

the cocktails

I had high hopes of tasting some great cocktails while in Vegas, but I was initially disappointed. While in search of the perfect Negroni - a classic gin-based cocktail - @kt_canfield had the following exchange with a bartender at Caesar's Palace:"What's your favourite cocktail to make?"

"That depends on the base spirit."

"Gin."

"Oh, the problem with gin is that there aren't many things you can mix it with."

Silence.

"So can you make a Negroni?"

"Yes, I can do that."

|

| Herbs and Rye cocktail menu |

Las Vegas is a brash city that takes some getting used to and working out. It's a large, disorderly, fun, chaotic, and superficial release from everyday realities. At its best when it doesn't take itself too seriously, Vegas embraces everything that is ridiculous and makes the ridiculous spectacular. I liked Las Vegas the most away from the glitzy glamour, when it felt more genuine and that's why I'd return - to discover more of what lies beyond the surface razzmatazz.